Don’t do math (can’t). But do do grammar. (Notice I violated grammar here because I can. I'm so good…the grammar police always give me a pass.)

Don’t do math (can’t). But do do grammar. (Notice I violated grammar here because I can. I'm so good…the grammar police always give me a pass.)

I believe in grammar—its rules for clarity of expression—so others can make sense of what we try to say.

Nonetheless, there is one grammatical rule that needs to go: the "m" in the objective case of the pronoun "who" … that would be "whom."

That m is a nasty, pretentious little hold over from the days when Latin was the sine qua non (see "bees knees") of language.

It's along the same lines as that other silly rule about never ending a sentence with a preposition. And we all know what THAT led to: Winston's famous quip, "THIS IS SOMETHING UP WITH WHICH I WILL NOT PUT."

WHO WHOM—The test

THIS? — Give the award to WHOEVER deserves it.

Or this? — Give the award to WHOMEVER deserves it.THIS? — Give the award to those WHO you think deserve it.

Or this? — Give the award to those WHOM you think deserve it.

The who / whom imbroglio is overrated. Clarity can be achieved perfectly well without that niggling little letter. Who? Whom? Does it matter? We get the point.

The answers

Read at your own peril.Answer: Give the award to WHOEVER deserves it.

“Whomever” is not the prepositional object of “to.” Rather, WHOEVER is the subject of a dependent clause, “whoever deserves it.” The entire clause is the prepositional object. Phew!Answer: Give the award to those WHO you think deserve it.

“Whom” is not the object of “you think…whom.” “You think” is parenthetical…you can remove it altogether. So the “who” becomes a relative pronoun for “those” and the subject of the relative clause “who deserve it.”

See what I mean? So much ink spilled over a measly m!

The rules of grammar, in this particular case, are uselessly arcane. It's like being a guest at an EDITH WHARTON dinner party while you try to figure out THE OYSTER FORK… from the FISH FORK… from the SALAD FORK… from the DESSERT FORK. We all have better things to worry about.

So here’s my personal campaign for a better world: let's TRASH THE m in whom!

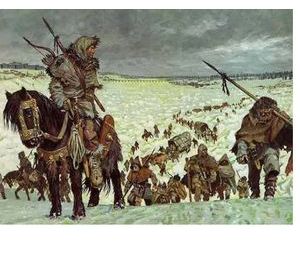

Oh, those feisty Indo-Europeans. Located some 4,000 years ago on the grassy steppes of Eurasia, just north of the Black and Caspian Seas, this ancient group of people gave us the English language—not just our language but nearly all of Europe's and India's, too.

Oh, those feisty Indo-Europeans. Located some 4,000 years ago on the grassy steppes of Eurasia, just north of the Black and Caspian Seas, this ancient group of people gave us the English language—not just our language but nearly all of Europe's and India's, too.

So how did the language of an isolated tribe of nomadic herders come to dominate so vast a territory? The answer is horses—and a human genetic mutation.

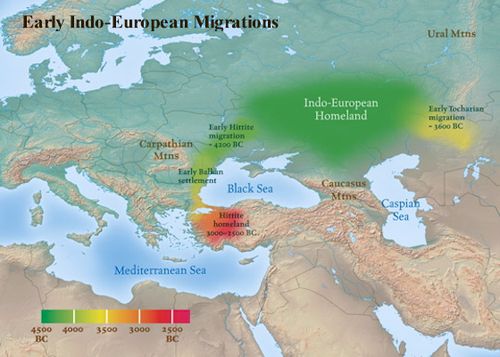

Map by Louis Henwood for The History of English Podcast

Horses were indigenous to the Eurasian grasslands, and the Indo-Europeans used them for meat—at first. But some bright (and brave) soul figured out that horses could be ridden and used for herding sheep and cattle. Once on horseback, the Indo-Europeans found they could raise and control larger and larger herds.

Another bright soul realized that instead of killing off so many goats or sheep for food, they could spare some and use their milk. Happily, that idea coincided with the spread of an errant gene—a mutation that produced lactase, the enzyme enabling humans to digest milk.

As a result, the herds thrived—as did the tribespeople, who grew in number and stature. The increase in herds and people gave way to the need for more land—and thus began the trek eastward to India and westward to Europe.

Map by Louis Henwood for The History of English Podcast

And if you were in their way? Well, they had horses—and you didn't—so you can guess who ended up with the land. Nonetheless, historians aren't sure how warrior-like the Indo-European tribes were, whether they always conquered or sometimes settled in peacefully. Most likely both.

However it happened, the Indo-Europeans came to dominate the inhabitants of their new lands. Their language continued to spread eastward and westward over thousands of years and thousands of miles, morphing into separate dialects...and eventually into separate languages, including the early Germanic languages, the ancestor of our own.

What this means, astonishingly, is that today about 50% of the world's population speak an Indo-European-derived language—3 billion of us—all from an ancient tribe of nomadic herders!

* This—and more, much more—is available on Kevin Stroud's wonderful podcast, The History of the English Podcast. Please take a week or two (or a month or two) to listen to his 50+ episodes. Stroud is a wonderfully lucid presenter and has put together a fascinating, detailed history of why our crazy language, English, is the way it is. If you love history and English, you'll be addicted. I am.

Also note the beautiful maps Stroud uses—two of which are included here. They were created for him by Louis Henwood. Thanks to both Kevin and Louis for their kind permission to use them.

Aah, look at Semiramis now—she's so much happier now that you've made a bit of progress in your mastery of the semicolon.

Aah, look at Semiramis now—she's so much happier now that you've made a bit of progress in your mastery of the semicolon.

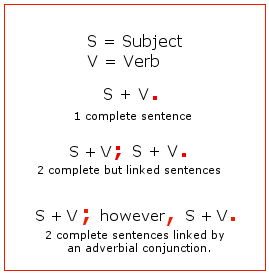

For a refresher scroll down to the previous post. Remember: the gist of the semicolon is that it connects two sentences without using a comma and a conjunction (and, but, or, so, for nor, yet).

In our final lesson, we're using semicolons with conjunctions—words like however, therefore, or nonetheless. They're called ADVERBIAL conjunctions.

—Semicolons & ADVERBIAL Conjunctions—Why use a semicolon?

Remember: a semicolon connects two related sentences.Think of it as a combination of a period and a comma. Notice the mark has one of each—top & bottom.

What's a conjunction?

A conjunction is a word that "conjoins," or links, two complete sentences. Regular conjunctions—and, but, so, for or, nor, yet—require a COMMA before the conjunction.Example: The dog barked , and the cat hissed.

Example: The dog barked , but the cat stood its ground.

Example: The dog barked , so the cat ran.What's an adverbial conjunction?

Like regular conjunctions, adverbial conjunctions link two full sentences—but with a SEMICOLON before and a COMMA after. They're "adverbs" in that they describe precisely how the 2nd sentence relates to the 1st—the same way adverbs describe verbs. Remember adverbs?—> She ate. How did she eat? She ate SLOWLY.

—> He sang. How did he sing? He sang LOUDLY.

Some common adverbial conjuctions

also however nevertheless anyway indeed nonetheless consequently instead now finally likewise otherwise further meanwhile then furthermore moreover therefore

Examples—

• It was too cold to enjoy the game ; however , she decided to go anyway.

The adverbial conjunction "however" indicates that the 2nd part of the sentence is in OPPOSITION to the first part. You could also use...nevertheless or nonetheless or still.

__________

• It was too cold to enjoy the game ; therefore , she decided not to go.

The adverbial conjunction "therefore" indicates that the 2nd part of the sentence is a CONSEQUENCE of the 1st part. You could also use...as a result or consequently.

__________

• It was too cold to enjoy the game ; furthermore , she didn't feel well.

The adverbial conjunction "furthermore" indicates that the 2nd part of the sentence is an ADDITION to the 1st part. You could also use...also or moreover.

__________

• It was too cold to enjoy the game ; instead , she went to the library.

The adverbial conjunction "instead" indicates that the 2nd part of the sentence is an ALTERNATIVE to the 1st part. You could also use...rather.

CAUTION

Don't confuse adverbial conjunctions when they're used as strict ADVERBS. Notice that in the following sentences they're offset by COMMAS. There's not a semicolon in sight.

• It was too cold, however, for the game.

• However, it was too cold for the game.

"However" functions as an ADVERB—not an adverbial conjunction—because there is only one sentence here (S + V): "It was"...

__________

• She did not, therefore, want to go to the game.

•Therefore, she did not want to go to the game.

"Therefore" functions as an ADVERB—not an adverbial conjunction—because there is only one sentence here (S + V): "She did (not) want"...

__________

• Furthermore, she did not feel well.

"Furthermore" functions as an ADVERB—not an adverbial conjunction—because there is only one sentence here (S + V): "She did (not) feel"...

People...! What is wrong with you? Never have so many understood so little about a mere SQUIGGLE on a page.

People...! What is wrong with you? Never have so many understood so little about a mere SQUIGGLE on a page.

Meet Semiramis, warrior princess of Assyria, ruler of the semicolon. She is here to HELP you. You will not refuse her.

Have faith. With a little guidance, you too can master the SEMICOLON—which means that you can don the costume and bear the title "Semiramis of the Semicolon." (Spear not included.)

—Semicolons—

Why use a semicolon?

A semicolon connects two sentences.Think of it as a combination of a period and a comma. Notice the mark has one of each—top & bottom.

Why not use a comma?

The comma is a 90-pound weakling. It's far too weakit can't hold two sentences together.

If you use one, you've got yourself a nasty little comma splice.Why not use a period?

You can. Use a period to end the first sentence. Then start the second sentence.The comma is too weak . It can't hold two sentences together.

When do you use a semicolon?

Sometimes you want to link ideas—two sentences that are related to one another. In that case you can use a semicolon.The comma is too weak ; it can't hold two sentences together.

A semicolon is strong ; it can hold two sentences together.What is a sentence?

A sentence is a complete thought. A period signals the end of that thought. A semicolon can extend the thought—by linking it to another complete but related thought.

Remember—

You must have two complete sentences in order to use the semicolon — S + V on the left ; S + V on the right.

Example—you have two (related) ideas...

Use 2 sentences —> with a period:

• It was too cold to enjoy the game . She decided not to go.

Use 1 sentence —> with a semicolon:

• It was too cold to enjoy the game ; she decided not to go.

________________

Example—you have two (related) ideas...

Use 2 sentences —> with a period:

• It was too cold to enjoy the game . However, she decided to go anyway.

Use 1 sentence —> with a semicolon:

• It was too cold to enjoy the game ; however, she decided to go anyway.

You don't have to use a semicolon to combine two sentences. You can also use a basic conjunction — and, but, so, for, or, not, yet — always (always, always) with a comma.

• It was too cold to enjoy the game , so she decided not to go.

• It was too cold to enjoy the game , but she decided to go anyway.

• It was too cold to enjoy the game , and she didn't want to go anyway.

It's no secret English is tough to learn. Some of it has to do with homophones and heterophones We've had fun before with words that sound alike but have different spellings and meanings—homophones, like bare and bear.

It's no secret English is tough to learn. Some of it has to do with homophones and heterophones We've had fun before with words that sound alike but have different spellings and meanings—homophones, like bare and bear.

This time we've got heterophones—also known as heteronyms—words that look alike but have diffferent pronounciations and meanings.

Don't You Just ♥ Words?

—Heterophones—

- Clara wound a bandage around his wound.

- Every number makes my mind grow number.

- The dump is full. Sorry, we must refuse your refuse.

- Don't desert me in the desert.

- Startled, the dove dove into the bushes.

- It's ugly, but I don't object to the object.

- No time like the present to present a good idea.

- The oarsmen had a row about how to row.

- She was too close to close the door.

- A handsome buck does like his does.

There are lots of double words with different meanings. Some are spelled alike but sound differently (desert/desert) ... others sound alike but are spelled differently (ore/oar/or). Try a few on your own. It's a fun game for book clubs...or any wordsmiths.