|

How to Read: Plot Reading |

| LitCourse 6 How to Read: Plot |

1 |

|

Plot—not as easy as it looks Your excellent dream

You corral your friends together to tell them about a dream you had the other night. But wait...you're not half-way through when you begin to notice eyes glazing over. They're bored? How could they be? The dream was... incredible! Huh. Maybe it's how you're telling it. |

|

| LitCourse 6 How to Read: Plot |

2 |

|

Plot—not as easy as it looks Structure–the shape of a plot

Chronology—the timeline of events Conflict—the element that creates tension Revelation—the information revealed to readers. |

|

| LitCourse 6 How to Read: Plot |

3 |

|

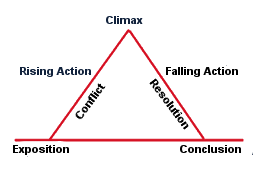

Plot—structure (classic)  |

|

| LitCourse 6 How to Read: Plot |

4 |

|

Plot—structure (classic) Exposition—background information; usually at the beginning, but not always.

Rising Action—series of events involving conflict, which creates tension and suspense. Climax—the peak, or high-point, of tension, a turning point in the action. Denouement—the falling-off of action after the climax; the conflict finds resolution. Conclusion—a wrap-up, sometimes epilogue. |

|

| LitCourse 6 How to Read: Plot |

5 |

|

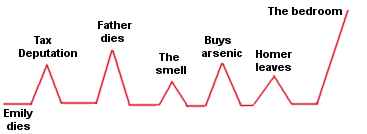

Plot—structure (nonconventional)

|

|

| LitCourse 6 How to Read: Plot |

6 |

|

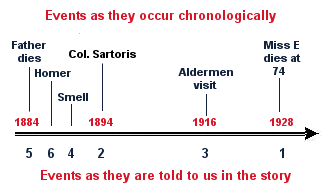

Plot —chronology Linear time—forward forward movement of time; events move from past to present.

Non-linear time—forward and backward movement of time. The telling of events is disjointed, jumping back and forth between past and present. "Well, this happened...but before that, this happened...." |

|

| LitCourse 6 How to Read: Plot |

7 |

|

Plot —chronology The next slide shows (1) events as they occur in time and (2) the same events as told to us in the story. The story starts in 1928 with Miss Emily's death...goes back to 1884...then forward to 1916... and so on. (All dates, except for Col. Sartoris's visit in 1894, are approximate.)

|

|

| LitCourse 6 How to Read: Plot |

8 |

|

Plot—chronology

|

|

| LitCourse 6 How to Read: Plot |

9 |

|

Plot—Conflict • Internal conflict

• External conflict |

|

| LitCourse 6 How to Read: Plot |

10 |

|

Plot—Conflict External conflict: pits characters against . . .

• other characters • the community—its people, ideals, or traditions • nations or other political structures • nature—weather, disease, natural landscapes, or natural disasters. Internal conflict: a struggle within a character • psychological, emotional, or spiritual turmoil Authors frequently use a combination of internal and external conflict in the same story. |

|

| LitCourse 6 How to Read: Plot |

11 |

|

Plot—revelation • Exposition

• Flashbacks • Foreshadowing • Suspended revelation |

|

| LitCourse 6 How to Read: Plot |

12 |

|

Plot—revelation Exposition—an explanation providing background information—events that occurred prior to the onset of the story. It may come from a narrator, dialogue, or a character's internal thoughts. Usually, but not always, at the beginning.

|

|

| LitCourse 6 How to Read: Plot |

13 |

|

Plot—revelation Flashbacks—also provide background information. They differ from exposition in that they take the form of an actual re-enactment of events. They come from characters' dreams, reveries or memories.

|

|

| LitCourse 6 How to Read: Plot |

14 |

|

Plot—revelation Foreshadowing—an event or piece of dialog that hints at what is to come, a precursor or "pre-echo" of future events. Foreshadowing is subtle, often more obvious in hindsight or upon re-reading.

|

|

| LitCourse 6 How to Read: Plot |

15 |

|

Plot—revelation Suspended revelation—authors withhold (or suspend) information to create suspense and surprise. Readers know only what the author wants to reveal...and when. Mystery plots are based on this technique, but all stories use it.

And now . . . |

|